I came home to four months of nothingness and a room that had been converted into a storage locker. Somewhere beneath the chaos, that was my room, lay my books—240 volumes that had shaped me, challenged me, and nearly broke me in some cases. Dostoevsky's White Nights, which I'd pushed on everyone during my peak fandom phase. The Nassim Taleb books I wouldn’t stop quoting. The Freud books that wouldn't let me sleep at night. The Top Gear magazines I'd wouldn't lay down as a kid, dreaming of engineering fast machines. Heavy new books from IIMA, that I haven't even opened yet.

They deserved better than cardboard boxes (not you, IIMA books). They earned a place that I can proudly display. They earned a place that will outlast me.

After passing 15 very long days with well over three months ahead, I finally decided to start the project I had been putting off for a long time: building a shelving system that would be worthy of the objects that had made me who I am. Moreover, I had told many people that I planned to build something during my vacation. So, I had to start.

The starting point of the design was, of course, the 606 Universal Shelving System, which Dieter Rams designed in the 1960s. I have been fanboying over Dieter Rams for over 5 years now—I even wrote an essay on this guy for a business history course at IIMA. I sincerely believe that every person involved in designing or building a product, whether digital or physical, needs to understand Dieter Rams' design philosophy and absorb his body of work. His work at Braun is well known and has certainly overshadowed his fantastic work in furniture design. I came across this product in 2022, and it was love at first sight.

But this project wasn't just another design homage project. Every object I planned to house in my system held what Jung called "numinous," meaning deep, symbolic significance that was part of my identity. The system needed to honor that – and the original 606 design does. That's why it was my baseline.

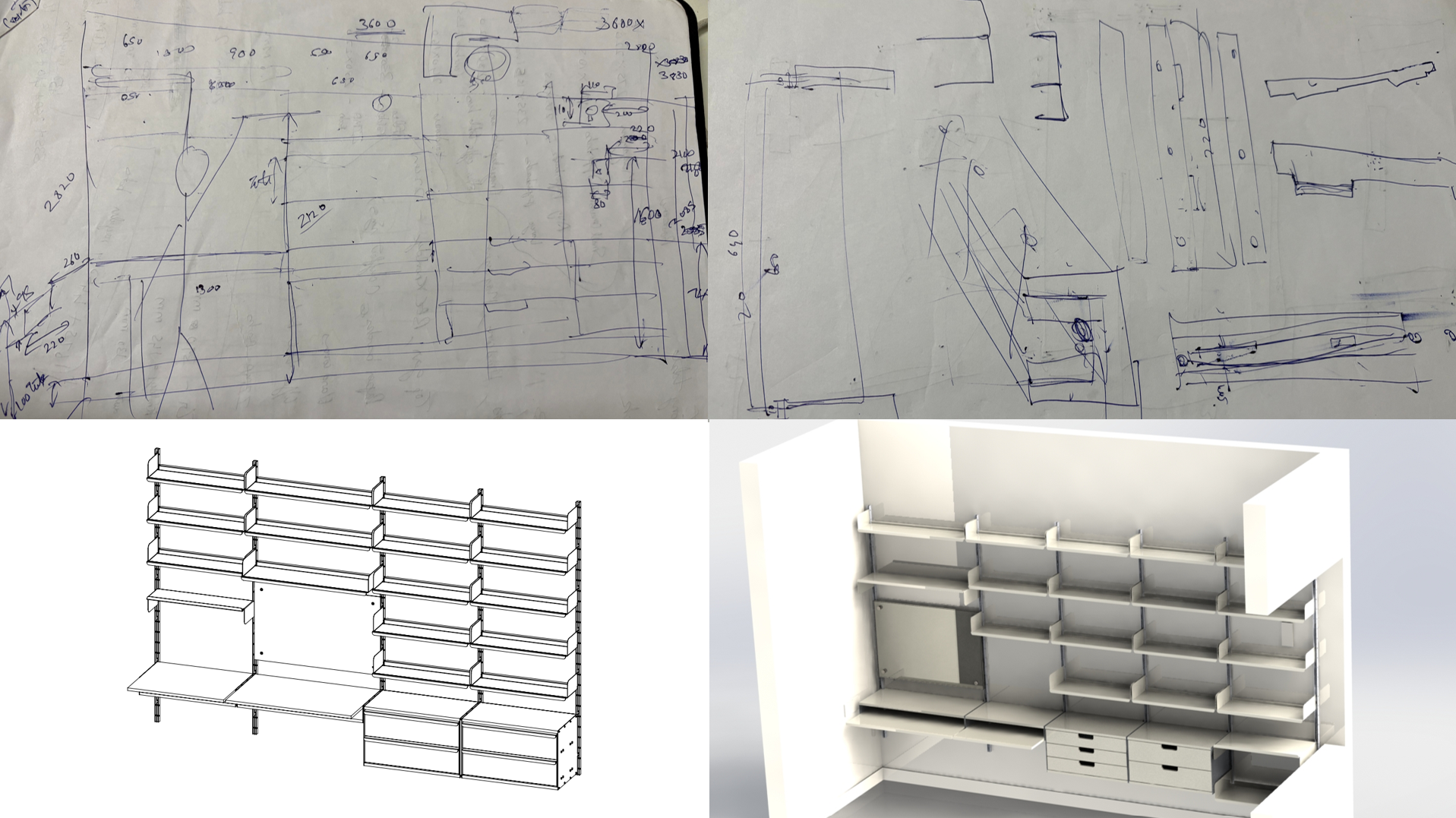

Design

I had only a few website pictures and a brochure to start with, and I also wanted to add my twist to the product. However, as I began, I soon discovered that the product's design was remarkably simple. So elegant and straightforward that I couldn't add or remove much from what Dieter Rams designed in the 1960s, yet it incorporated many of my own engineering and design elements.

On the requirements side, I needed space for approximately 240 books and 7 years' worth of Top Gear, 4 years of BBC Knowledge, some old encyclopedias, and those brand-new, yet heavy, books from IIMA. Overall, I needed a shelf space of 6200 cm, and another 6200 cm for further expansion. But more than storage, I needed a system that would grow with me—as we live through our years, more meaningful objects inevitably accumulate, each one deserving its place in our personal universe.

Beyond books, I also needed a desk for my upcoming WFH job and some drawers for good measure. For the desk, I wanted one that was at least 1.2 to 1.4 meters long—I had loved my long and wide desk at IIMA D21. I also loved the pinboard at my dorm room, but it wouldn't look upscale enough for my design, so I chose to design a glass board instead. However, the most important criterion was that the system must last as long as my house does, while also allowing me to reconfigure and expand whenever needed.

Entering the design process, many people have misconceptions about the word 'design' and use it where it doesn't convey its intended meaning (especially "designing a strategy" or "designing a policy"). A pure design process is often just about anticipation, optimization, and taste. Anticipation of how it will be manufactured, stored, transported, used, and even misused. Good design borders on prescience in this lens. Second is optimization of material, cost, features, and weight, under a set of functional requirements. The third, taste, is subjective, but it's not about fancy aesthetics—instead, it influences the choices a designer makes when all options are equally good.

When it comes to designing systems rather than parts, uncertainty arising from complexity makes the "anticipation" part nearly impossible. Unlike tech products, where you can design, ship, evaluate, and iterate quickly, hardware evolution is sluggish, taking years if not decades. Therefore, when designing a system, it's better to retain some aspects as intended by the designer, and leave the rest organically customizable. A good analogy would be city planning—a totally planned city is bound to fail, but the right level of planning combined with good judgment on what to anticipate and what to leave open leads to livability.

For the most part, I designed the system with my notepad, SolidWorks (CAD), and Ansys (Structural analysis). Using these tools after so many years brought me so much joy, especially after confirming "I still got it." Oh yeah, that’s a special feeling.

One of the foremost high-level decisions was the width of each rack bay and overall configuration. My room was 12 ft wide, and I wanted a wall-to-wall setup. The longest I could keep a bay without structural weakness was about a meter. But having all wide bays wouldn't help because I wanted to categorize my books. So, I opted for five bays total: four 650mm bays and one 850mm bay. This also allowed me to create more designs and test more unique parts if I chose to scale production later - and my friend, Goharnath (AKA the US guy), wouldn't like anything better. He has already been bullying me to start a company so that he can come back home and go directly to the "C-suite."

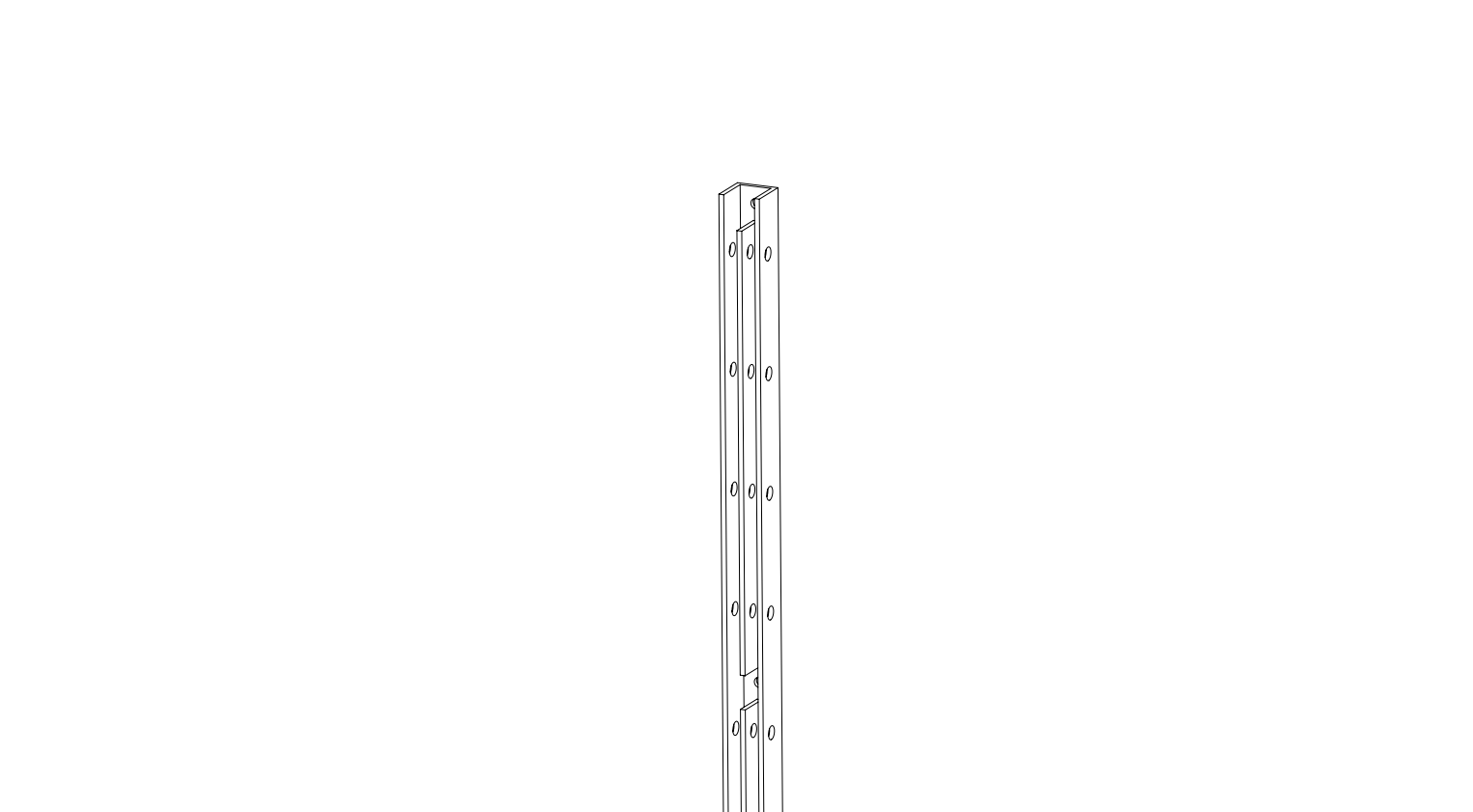

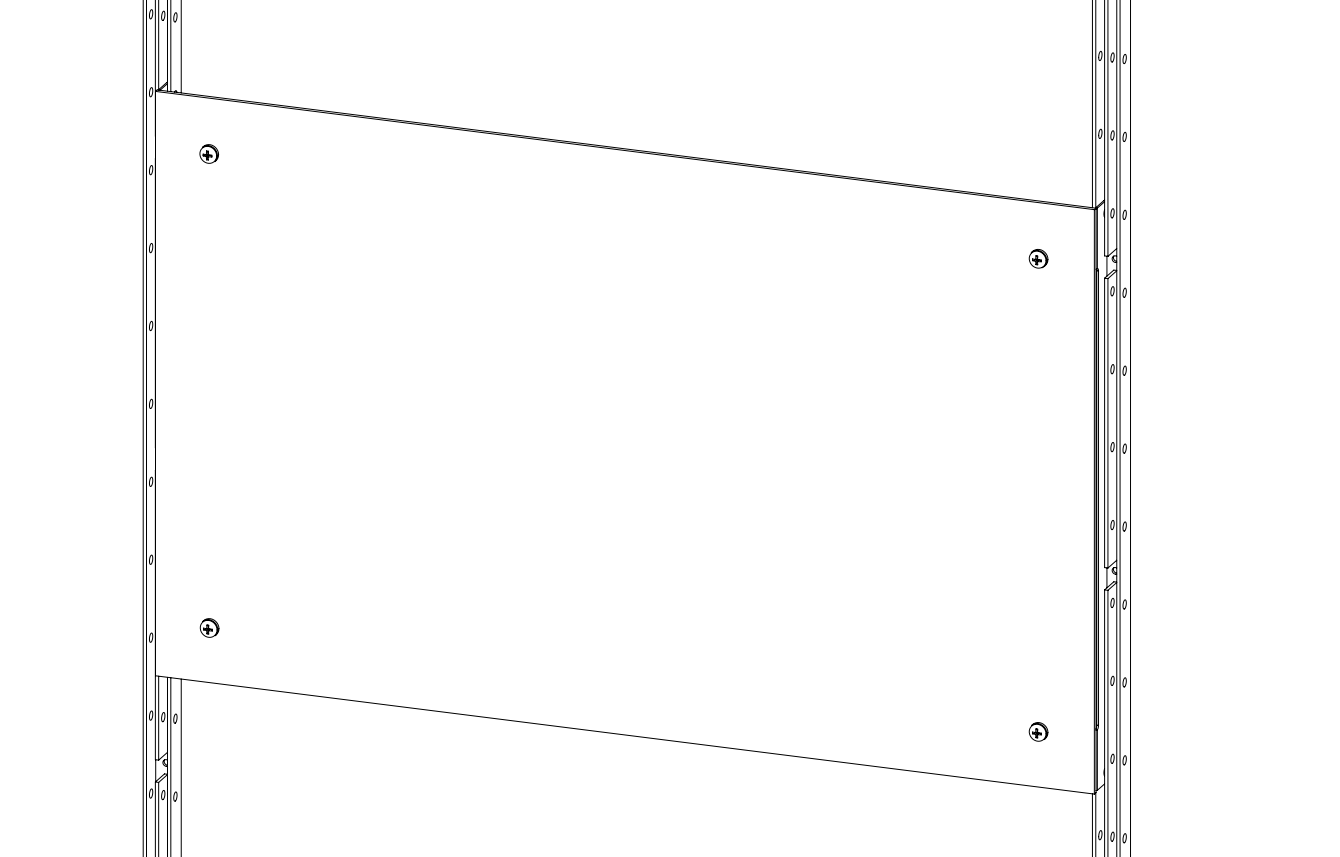

Aluminum E-rails

The most critical part of the whole system is the wall-mounted rails. Everything depends on their strength, parallelism, and mounting rigidity—if any part were to fail, it would be this one. The weakest points had to be carefully engineered.

I had several options for mounting the racks on the rail—ratchet, clip-ons, fasteners—but all had problems in either longevity or elegance. So, I went with the original 606 design, an invisible grooved pin, although it skyrocketed my costs (35% of my overall costs). Some things are worth the investment.

Another early design choice was the mounting mechanism. I had several options for mounting to a concrete wall, but settled on a male-type Fischer brand 50mm wall anchor—a decision that seems mediocre in hindsight, as I would soon discover.

I wanted to make the E-rails as a monolithic structure, but given my small requirement, I couldn't do extrusion, and machining was too expensive, so I had to recreate the part using multiple manufacturing processes:

C Standard extrusion → Milling and drilling on the sides + Laser cut center pieces → joining the two with fixtured welding, finishing.

Since this was the first part I had manufactured, I embarrassed myself in front of manufacturing professionals by using the wrong standards and improper drawing files—absolute amateur errors. However, I found excellent manufacturing personnel for machining and welding. It was a grueling process with multiple points of failure, especially the welding. I had to do a lot of welding engineering sorcery to prevent these 1.8-meter-long rails from bending like, to use the welder's language, Arjunar's Bow.

Between all these processes, I spent at least 20 hours filing and sanding—a ruthless task that left my hands raw but my mind clear—and Abhijit’s Techno mixes and Fred Again Actual life (1,2, &3) helped along the way, too. There's something meditative about perfecting every surface because you care about it. The whole process went relatively smoothly and finished with the expected quality and timeframe.

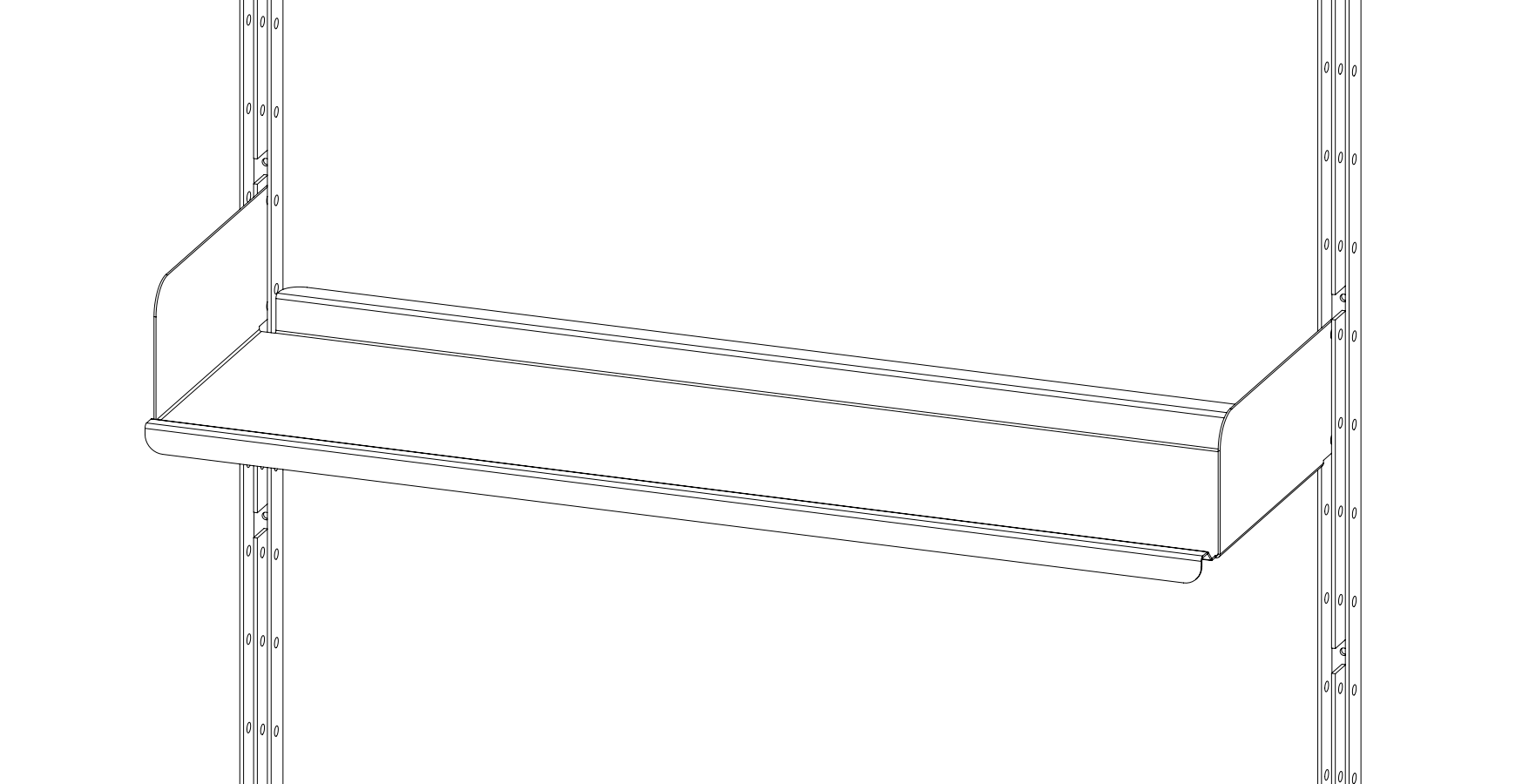

Steel Rack

On the design front, the original 606 rack was the most beautiful of the lot in the product's catalog. It is honest to the extent of being unimaginable—the product has only everything it needs to satisfy its function, nothing more and nothing less.

While the E-rails were complex to manufacture, yet completed quickly, the racks were rather rudimentary and still stalled the project for over a month. I also made the amateur mistake of not thoroughly evaluating the tool set that my laser-cut guy had. I created two incorrect design iterations, and the whole project cost way more time and money than it should have. There were three weeks where this laser-cutting guy was the first person I spoke with every morning—honestly, rather embarrassing. Each incorrect bend, failed prototype, and production delay felt like a small betrayal of my grand plan. But you have to grind through if you hope to reach the finish line.

However, once the laser cutting and CNC bending were completed, the powder coat (cream white, RAL 9002) finish emerged quickly and beautifully. Moreover, all hail my new 2009 Honda Jazz with its 1,250-liter boot space—making logistics some of my easier, cheaper, and more enjoyable tasks.

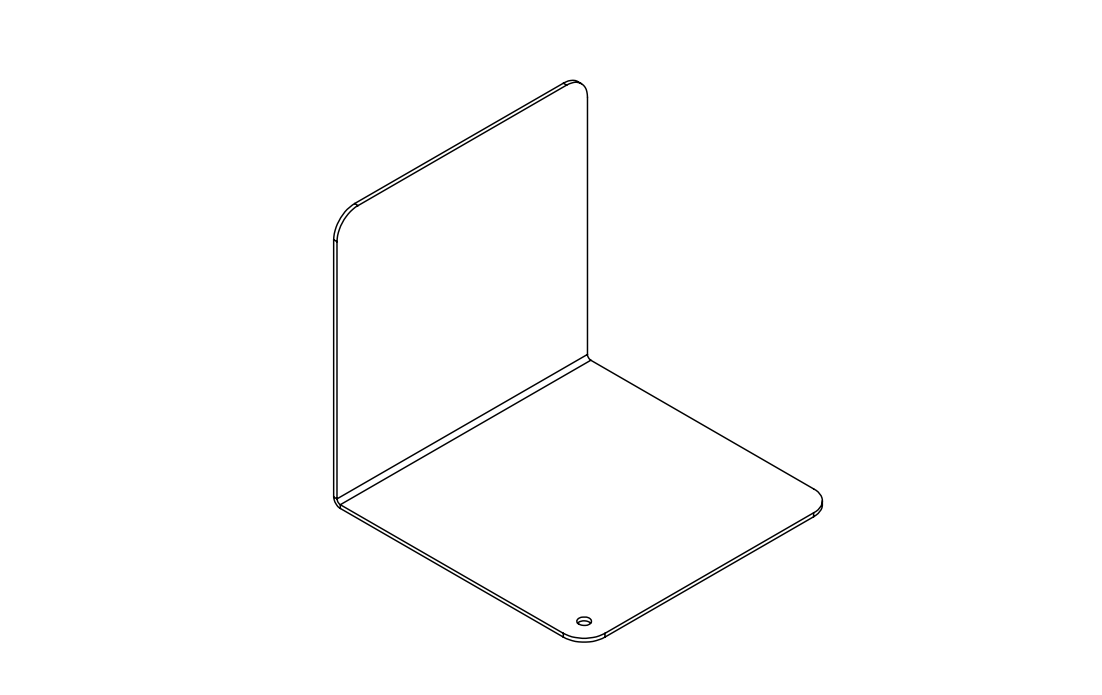

Bookends

It's an elementary part—a simple, rectangular laser-cut plate with one 90-degree bend. Yet it's probably my favorite design element in the whole system, and here's why: the small punch hole in the bottom right corner.

It exists for one solitary purpose. When powder coating, we cannot place the bookend on the floor and coat it with color powder—it spoils the finishing. This single hole allows the powder coaters to hang it using a metal wire and apply powder coating uniformly throughout. Such an exemplary piece of anticipation from me, if I do say so myself. Sometimes the tiniest details carry the most satisfaction.

Assembly

This is where the decision to use 50mm Fischer anchor bolts came back to haunt me. So many incorrectly drilled holes (which we had to refill), and so many anchor bolts that slipped (which we could do nothing about). However, I didn't have to worry about parallelism, as I had designed fixtures that facilitated mounting in parallel, and I used a bubble level (such an elegant device—an iPhone's level tool couldn't even come close) to evaluate the alignment.

As each rail clicked into place, perfectly parallel and ready to bear weight, I wasn't just mounting hardware—I was creating a permanent home for the ideas that had shaped me, in a system that shaped my last few months. With this, the first phase was done, and this was already mid-June.

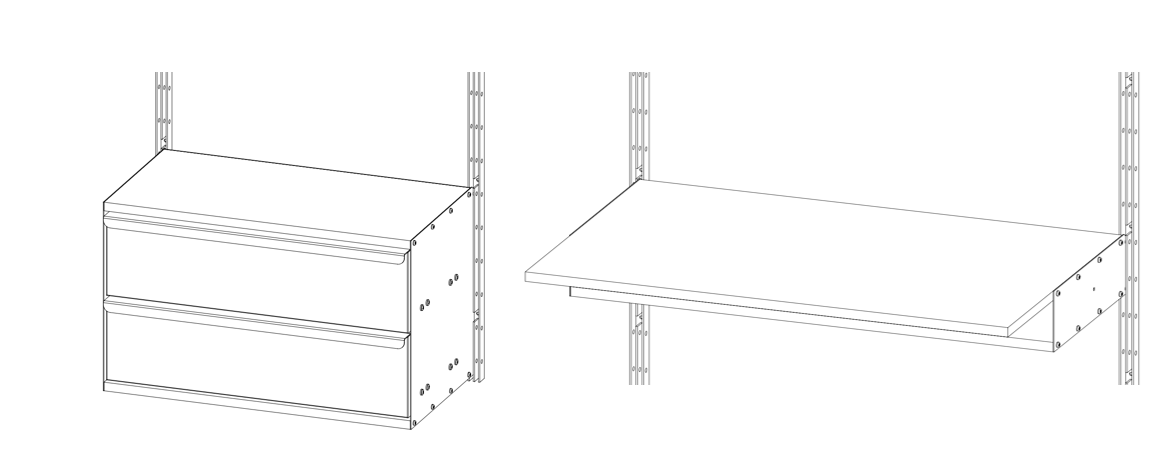

Drawers & Desk

With the core structure complete, I faced my biggest unknown: working with wood. I kept the drawers and desks for last because I had zero experience in carpentry. The processes, techniques, finishing, and tolerances are entirely different for wood parts. But here, I was building semi-wood drawers to be mounted to aluminum rails. There was a lot to learn and design.

The choice came down to getting a good finish on the edges (literally). I had two options—MDF with painting or waterproof plywood with laminate and edge banding. I could only choose the same process for the desk and drawers, because we could only buy plywood or MDF in 8x4 feet sheets (one sheet was enough for both). I chose the easier option of plywood with laminates and edge banding, slightly compromising on finishing quality but getting better tolerances.

The design wasn't straightforward because many dimensions were fluid, and it had numerous components requiring hand manufacturing—the root of all dimensional errors. I also had to design several laser-cut fixtures to reduce my dependency on human carpenters. The final design consisted of 70% metal parts for precise tolerances, with the top and front parts made of wood for a finished appearance. The side plate also had 16 exposed M5 pan head machine screws, making the design more honest and giving it an industrial look. I also procured premium Hettich 300mm drawer slide mechanisms with soft-close function that work like a charm.

The wood cutting and edge banding process proceeded rather smoothly, with tolerances of ±1mm (satisfactory for wood).

Now, the crucial part - carpentry assembly. Luckily, I found a good carpenter quickly. That day was probably the most productive of the entire project. I took my dad with me as well. The carpenter was so skilled that he understood exactly what I needed and the fixtures I had designed. In 2 hours, all my drawers and desks were built. There was even a wedding happening across the road, giving us the soundtrack—proper Tamil banger songs. We loaded everything into my car, came back home, and mounted them in 10 minutes. Sometimes the universe aligns perfectly.

Glass Board

The glass board was a bit of an extravagance. I'm not even sure whether I'll use it. But Vijay Prabu, a new IIMA grad, can afford this extravagance. It made the whole system look very upscale. It's quite a simple product with just 4 or 5 parts, and honestly, it didn't cost much at all. 10x aura boost for the money I spent - a good deal indeed.

On July 15th, the project was completed.

Final Outcome

Before IIMA, my room had a bed, a small shelf for my books, a mat, and a desk. However, after I left, they converted my room into a proper storage room, so when I returned with my boxes from IIMA, this was the state of affairs. Utter chaos.

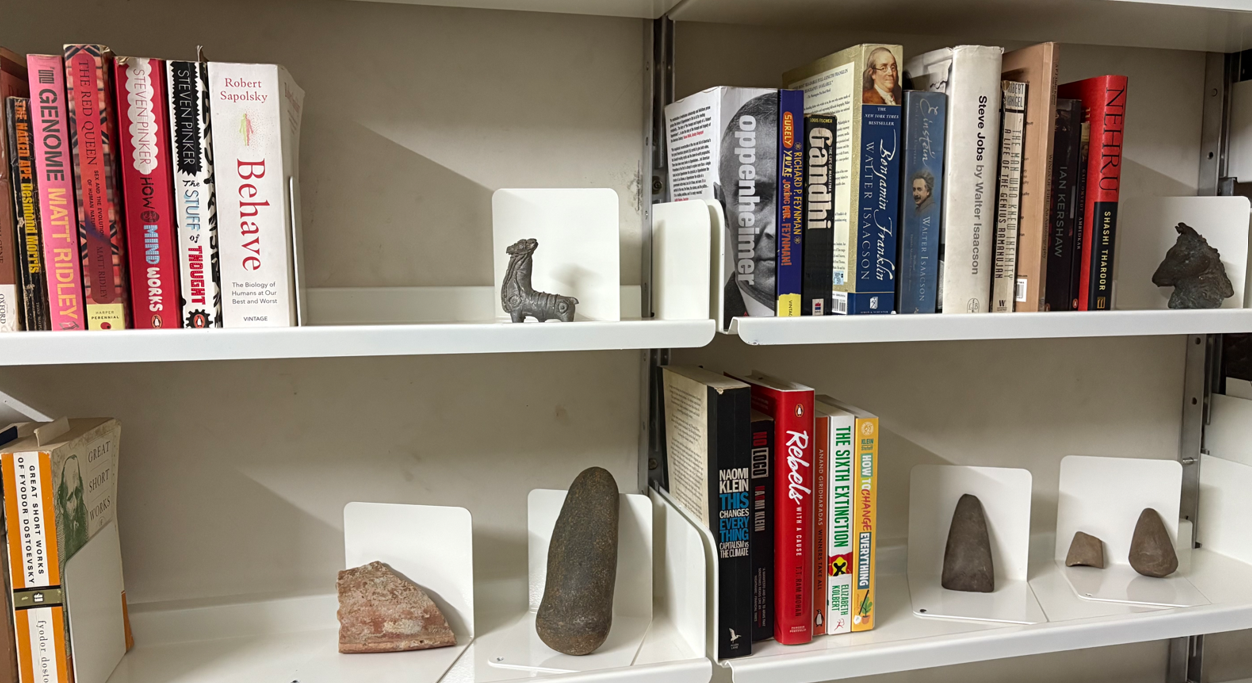

This was the final outcome.

I guess, the lighting could be much better, but interior work is a rabbit hole with no escape—and this obsession is probably more ideal for a mid-life crisis. By the way, indoor plants are a scam, or at least very high maintenance. Guess what? Green plants need sunlight for photosynthesis!

The System

As I developed this system, I spent considerable time meditating on its design philosophy, and it brought me back to that Jungian concept that I mentioned earlier.

"Numinous" or "Numinosity" refers to objects that hold deep, symbolic, spiritual, and mysterious meaning for an individual. Over a lifetime, we collect such objects, store them, and want to showcase them to the world, because they hold meaning that's part of our identity. All of us do this, however materialistic, stupid, and ridiculous the idea of deriving meaning from objects might sound.

I've had an SKF SA6E forged rod end bearing on all my keys since 2020—suspension parts from the racing cars I was building. A close friend hugs a stuffed dog every night to sleep. My sister collects Despicable Me Minion dolls. Who are we to judge?

When storing and displaying such objects, you want the objects to be the hero, not the storage system. The system should ideally disappear, becoming invisible infrastructure for meaning.

As we live through our years, more meaningful events occur, inevitably leading to more numinous objects. So, the shelving system must be designed to grow with you.

But most importantly, we all wish to keep our numinous objects with us, at least until we're alive, ideally for as long as possible. For the objects to stay alive, they need a place, and therefore, the system must also be alive for much longer than an individual's lifespan.

I think my system does all of the above. Moreover, it holds all my books—some of which permanently changed my life for better or worse, many mid-level ones, and a few I'm not even proud of owning. It holds my old encyclopedias and Top Gear magazines that I spent countless hours reading as a kid. It houses stolen parts from our Formula Student lab, my roller skates that took me to nationals, my first binoculars, our IIMA projector & my Swiss knife (shoutout to Abhijit), artifacts from my Dholavira excavations, and so much more.

Most importantly, it brought me joy and purpose at a crucial time when I had neither. I can even say this system rejuvenated me in more ways than one. It has rightfully earned its place as one of my most numinous objects—a close second behind my car parts. Absolutely worth it.

Comment